Machine Learning Model Accuracy: What’s Good Enough?

Machine learning model accuracy benchmarks: Learn what accuracy levels are acceptable, how to evaluate ML models, and when precision matters more than accuracy.

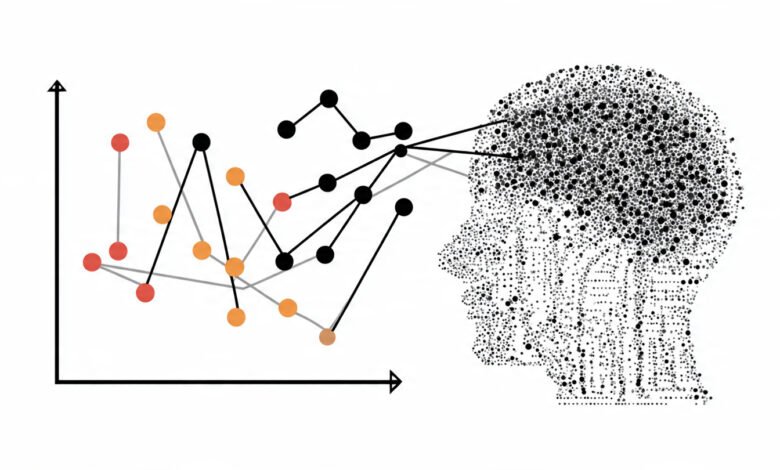

Machine learning model accuracy is often the first metric data scientists check after training a model, but it’s also one of the most misunderstood. You’ve built your model, run it on test data, and got 85% accuracy. Sounds decent, right? But is it actually good enough for your specific problem? The answer isn’t as straightforward as you might think.

The question “what’s good enough?” doesn’t have a universal answer because machine learning accuracy requirements vary dramatically based on your application, data characteristics, and business objectives. An 85% accurate model might be revolutionary in predicting earthquake locations, but dangerously inadequate for medical diagnosis. Context matters immensely in evaluating whether your ML model performance meets the necessary standards.

Many beginners fall into the trap of chasing high-accuracy numbers without understanding what those numbers actually mean or whether accuracy is even the right metric to optimize. Meanwhile, experienced practitioners know that model evaluation requires looking beyond a single percentage to understand precision, recall, F1 scores, and how your model performs across different subgroups of data.

This guide explores what constitutes “good enough” accuracy across various domains, why accuracy alone can be misleading, what other metrics matter, and how to determine appropriate benchmarks for your specific machine learning projects. Whether you’re building a spam filter, fraud detection system, recommendation engine, or medical diagnostic tool, you’ll learn how to evaluate your model accuracy properly and set realistic performance expectations that align with real-world requirements.

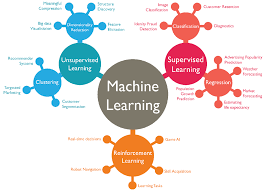

Understanding Machine Learning Model Accuracy

Machine learning model accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions out of all predictions made. It’s calculated as: (True Positives + True Negatives) / (Total Predictions).

If your model makes 100 predictions and gets 87 correct, your accuracy is 87%. Simple enough, right?

But this simplicity masks important nuances. Accuracy treats all correct predictions equally, regardless of whether they’re positive or negative cases, and all errors equally, regardless of their real-world consequences.

The Accuracy Formula

The mathematical representation is:

Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN)

Where:

- TP = True Positives (correctly predicted positive cases)

- TN = True Negatives (correctly predicted negative cases)

- FP = False Positives (incorrectly predicted positive cases)

- FN = False Negatives (incorrectly predicted negative cases)

This formula shows that accuracy considers both classes equally. In balanced datasets where positive and negative cases are roughly equal, this works reasonably well. In imbalanced datasets, however, accuracy becomes dangerously misleading.

When Accuracy Is Misleading

Imagine building a fraud detection model for credit card transactions. If 99% of transactions are legitimate and only 1% are fraudulent, a model that predicts “legitimate” for every transaction achieves 99% accuracy while catching zero fraud cases.

This is the accuracy paradox—high accuracy doesn’t guarantee a useful model, especially with imbalanced datasets.

Class imbalance appears in many real-world scenarios:

- Medical diagnosis (most people don’t have rare diseases)

- Fraud detection (most transactions are legitimate)

- Manufacturing defect detection (most products pass quality control)

- Spam filtering (legitimate emails often outnumber spam)

In these situations, alternative metrics like precision, recall, and F1 score provide better insights into model performance.

What Accuracy Is Good Enough? Industry Benchmarks

Determining acceptable machine learning accuracy depends heavily on your domain, the problem you’re solving, and the consequences of errors.

Medical Diagnosis and Healthcare

Healthcare applications demand extremely high accuracy because mistakes can literally cost lives. However, the acceptable threshold varies by application:

Screening tools for common conditions might accept 85-90% accuracy if they’re meant to flag cases for further review rather than make definitive diagnoses. The goal is catching most cases while accepting some false positives that doctors will filter out.

Diagnostic models for serious conditions typically need 95%+ accuracy, with particular emphasis on recall (sensitivity) to minimize false negatives. Missing a cancer diagnosis is far worse than a false alarm requiring additional tests.

Surgical robotics and treatment planning require near-perfect accuracy (98-99%+) because errors directly impact patient outcomes during procedures.

According to research from the National Institutes of Health, medical AI systems are increasingly held to standards comparable to or exceeding human expert performance, which varies by specialty but often ranges from 85% to 95% accuracy on diagnostic tasks.

Financial Services and Fraud Detection

Fraud detection models balance catching fraudulent activity against inconveniencing legitimate customers.

Credit card fraud detection typically operates at 90-95% accuracy, but precision matters significantly. Too many false positives mean declined legitimate transactions and frustrated customers. Financial institutions often tune models to accept slightly lower fraud capture rates to reduce false positive rates.

Loan default prediction models generally achieve 70-85% accuracy. The inherently unpredictable nature of human financial behavior makes perfect prediction impossible, and lenders account for this uncertainty in their risk models.

Money laundering detection prioritizes recall over precision since regulatory requirements demand a thorough investigation of suspicious activities. Models achieving 80-90% accuracy with high recall are considered effective.

E-commerce and Recommendation Systems

Recommendation engines have different accuracy expectations because recommendations are suggestions rather than critical decisions.

Product recommendations often achieve 60-75% accuracy in predicting what users will actually purchase. This sounds low, but successful recommendations don’t require perfection—they just need to perform better than random selection.

Content recommendations (videos, articles, music) target similar ranges. Netflix famously considers a recommendation system successful if users engage with 60-80% of suggestions, understanding that taste is subjective and unpredictable.

Search ranking algorithms aim for 80-90% relevance, meaning the top results should match user intent in most cases.

Autonomous Vehicles

Self-driving cars represent one of the most demanding applications for machine learning models because errors can cause fatal accidents.

Object detection (identifying pedestrians, vehicles, traffic signs) requires 95-99% accuracy depending on the object type and environmental conditions. Critical objects like pedestrians demand higher accuracy than less critical ones like distant buildings.

Path planning and decision-making systems need near-perfect performance (99%+) because a single error at highway speeds can be catastrophic.

The industry standard is that autonomous systems must demonstrate safety levels significantly exceeding human drivers, who cause approximately 1 fatal accident per 100 million miles driven in the United States.

Natural Language Processing

NLP applications show wide accuracy variation based on task complexity:

Sentiment analysis typically achieves 80-90% accuracy on simple positive/negative classification. More nuanced emotion detection drops to 70-80% due to language complexity and context dependence.

Machine translation quality varies by language pair, with accuracy between 70-90% measured by BLEU scores and human evaluation. High-resource language pairs (English-Spanish) perform better than low-resource pairs.

Named entity recognition achieves 85-95% accuracy on well-structured text but drops significantly on informal text like social media posts.

Question answering systems range from 70-90% accuracy depending on question type and domain specificity.

Manufacturing and Quality Control

Defect detection models in manufacturing typically target 95-99% accuracy because missing defects means shipping faulty products, while false positives waste inspection resources.

Predictive maintenance models achieve 70-85% accuracy in forecasting equipment failures. The inherent uncertainty in mechanical systems makes perfect prediction impossible, but catching 70-80% of failures before they occur still provides substantial value.

Beyond Accuracy: Other Critical Metrics

Model accuracy alone rarely tells the complete story. Understanding complementary metrics is essential for proper model evaluation.

Precision and Recall

Precision measures what proportion of positive predictions are actually correct: TP / (TP + FP). High precision means when your model says “yes,” it’s usually right.

Recall (also called sensitivity) measures what proportion of actual positive cases you correctly identify: TP / (TP + FN). High recall means you catch most positive cases.

There’s typically a trade-off between precision and recall. You can increase recall by classifying more cases as positive, but this increases false positives and decreases precision.

When to prioritize each:

Prioritize precision when false positives are costly:

- Spam filtering (don’t want legitimate emails marked as spam)

- Promotional offers (don’t want to give discounts to customers who’d buy anyway)

- Recommending expensive treatments or interventions

Prioritize recall when false negatives are costly:

- Disease screening (don’t want to miss cases)

- Fraud detection (catching fraud matters more than some false alarms)

- Security threat detection

F1 Score

The F1 score harmonizes precision and recall into a single metric: 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall).The

F1 score is particularly useful for imbalanced datasets because it considers both false positives and false negatives. A high F1 score (0.8-1.0) indicates strong overall performance across both metrics.

Weighted F1 scores account for class imbalance by calculating F1 for each class and averaging based on class frequency.

Confusion Matrix

A confusion matrix visualizes all four prediction outcomes (TP, TN, FP, FN), providing a comprehensive view of model performance.

Reading a confusion matrix reveals:

- Which classes does your model confuse most often

- Whether errors skew toward false positives or false negatives

- Whether performance varies across different classes

ROC Curve and AUC

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve plots true positive rate against false positive rate at various classification thresholds.

AUC (Area Under the Curve) summarizes ROC curve performance in a single number from 0 to 1:

- AUC = 0.5: Random guessing

- AUC = 0.7-0.8: Acceptable performance

- AUC = 0.8-0.9: Good performance

- AUC = 0.9+: Excellent performance

AUC is particularly valuable because it’s threshold-independent, showing overall model quality regardless of where you set the classification boundary.

Log Loss and Cross-Entropy

Log loss (logarithmic loss) measures prediction probability accuracy, not just classification accuracy. It penalizes confident wrong predictions more heavily than uncertain wrong predictions.

Models with lower log loss not only predict correctly but also express appropriate confidence in their predictions—crucial for applications where probability estimates matter.

Mean Absolute Error and RMSE

For regression models predicting continuous values, accuracy isn’t applicable. Instead, evaluate using:

MAE (Mean Absolute Error) averages the absolute differences between predictions and actual values. It’s easy to interpret in the original units.

RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) penalizes large errors more heavily than MAE. Use RMSE when large errors are particularly problematic.

R-squared measures the proportion of variance explained by your model, ranging from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate a better fit, though the acceptable threshold varies by domain.

According to the Association for Computing Machinery, selecting appropriate evaluation metrics based on problem characteristics is one of the most critical skills in developing effective machine learning systems.

Factors That Determine “Good Enough” Accuracy

Multiple factors influence what constitutes acceptable machine learning model accuracy for your specific application.

Cost of Errors

The relative costs of false positives versus false negatives dramatically shape acceptable accuracy thresholds.

Equal error costs allow optimizing for raw accuracy. If predicting whether a customer will click an ad, both types of errors have similar minor consequences.

Asymmetric error costs require careful consideration:

- Medical screening: False negatives (missed diagnoses) can be fatal

- Email spam filtering: False positives (blocking legitimate emails) frustrate users more than false negatives

- Loan approval: False positives (approving bad loans) cost money directly

Quantifying these costs helps determine optimal operating points even if overall accuracy isn’t maximized.

Dataset Characteristics

Your data fundamentally constrains achievable accuracy.

Class imbalance makes high accuracy easier to achieve but less meaningful. A 95% accurate model on a 95:5 dataset might perform no better than always predicting the majority class.

Data quality issues like missing values, measurement errors, or outdated information reduce maximum achievable accuracy regardless of algorithm sophistication.

Feature relevance determines whether your data contains enough signal to make accurate predictions. If features don’t correlate with outcomes, even perfect modeling yields poor accuracy.

Dataset size affects both achievable accuracy and the reliability of accuracy estimates. Small datasets may show high accuracy through overfitting while generalizing poorly.

Business Requirements and Constraints

Practical considerations often outweigh pure performance metrics.

Response time requirements may force the acceptance of lower accuracy for faster inference. Real-time fraud detection can’t use computationally expensive models that delay transaction approval.

Interpretability sometimes means choosing simpler, less accurate models whose decisions can be explained to stakeholders or regulators.

Resource constraints around computational power, memory, or deployment environment may limit model complexity and achievable accuracy.

Update frequency affects acceptable accuracy—models that retrain frequently can accept slightly lower accuracy because they’ll improve soon, while models frozen for months need higher initial accuracy.

Baseline Performance

Understanding baseline performance provides context for evaluating model accuracy.

Random baseline: What accuracy would random guessing achieve? For balanced binary classification, this is 50%. Your model must substantially exceed this.

Majority class baseline: What accuracy does always predicting the most common class achieve? Your model must beat this significantly to provide value.

Human expert baseline: In some domains, comparing ML model performance to human experts establishes meaningful benchmarks. Medical diagnosis, image recognition, and language translation benefit from these comparisons.

Previous model baseline: If replacing an existing model, the new model should meaningfully outperform the old one (typically 2-5% absolute accuracy improvement).

Regulatory and Compliance Requirements

Regulated industries face mandatory performance standards.

Healthcare AI must often demonstrate equivalence or superiority to existing diagnostic methods and receive regulatory approval from agencies like the FDA.

Financial services regulations may require minimum accuracy thresholds for automated decision systems, particularly those affecting lending or creditworthiness.

Legal and ethical considerations around fairness demand that accuracy remains consistent across demographic groups, not just overall.

How to Determine Your Accuracy Target

Setting appropriate model accuracy targets requires systematic analysis rather than arbitrary selection.

Start with Business Objectives

Define what success looks like from a business perspective before considering technical metrics.

Ask stakeholders:

- What problem does this model need to solve?

- What would manual processes cost without the model?

- What value does correct prediction provide?

- What harm do incorrect predictions cause?

- How much improvement over current methods is worth the investment?

Translate business objectives into measurable outcomes, then map those outcomes to model performance metrics.

Calculate the Value of Improvements

Quantify the business impact of accuracy changes.

If a fraud detection model at 90% accuracy catches $10 million in fraud, and 95% accuracy catches $11 million, the 5% improvement is worth $1 million annually. Compare this value against the cost of achieving that improvement.

For recommendation systems, calculate how the conversion rate changes with different accuracy levels. A 5% accuracy improvement might translate to 2% more purchases, directly quantifiable in revenue.

This value calculation helps determine how much accuracy is “good enough” by comparing improvement costs against benefits.

Benchmark Against Alternatives

Compare your model against existing alternatives:

Current process performance: If humans manually perform the task, measure their accuracy. Your ML model should match or exceed this, accounting for the volume increase automation enables.

Competitor performance: In competitive domains, research has published accuracy levels for similar problems. Matching industry leaders may be necessary for competitive parity.

Published research: Academic papers often report state-of-the-art accuracy on standard datasets, providing reference points for what’s achievable.

Run Pilot Tests

Test your model in controlled environments before full deployment.

A/B testing compares model predictions against current processes, measuring real-world impact rather than just accuracy metrics.

Shadow mode runs your model alongside existing systems without affecting outcomes, letting you validate performance without risk.

Gradual rollout starts with low-stakes decisions or small user groups, expanding as confidence in model accuracy grows.

Pilot testing often reveals that required accuracy differs from initial estimates once stakeholders see real predictions.

Consider Iteration Plans

Determine whether your initial deployment is the final version or the first iteration.

Continuous learning systems that update regularly can launch with lower accuracy because improvement is ongoing. An initial 75% accuracy that grows to 85% over three months may be preferable to delaying launch for an initial 80% accuracy.

Static deployments that won’t update for months or years need higher initial accuracy since you can’t rely on quick fixes.

Improving Machine Learning Model Accuracy

If your current model accuracy falls short of requirements, several strategies can help improve performance.

Gather More Training Data

Additional data almost always improves machine learning models, particularly when current datasets are small.

Synthetic data generation creates artificial training examples through techniques like SMOTE, augmentation, or simulation.

Active learning identifies the most informative unlabeled examples for human annotation, efficiently expanding training data.

Transfer learning leverages models pre-trained on large datasets, requiring less domain-specific data to achieve good accuracy.

Feature Engineering

Better features often improve accuracy more than algorithm changes.

Domain knowledge helps create meaningful features that capture patterns relevant to your prediction task.

Feature selection removes irrelevant or redundant features that add noise without signal.

Feature transformation (normalization, scaling, binning) makes existing features more useful for specific algorithms.

Interaction features capture relationships between variables that matter for prediction.

Algorithm Selection and Tuning

Different algorithms suit different problems, and tuning dramatically affects performance.

Algorithm comparison: Test multiple algorithm families (tree-based, linear, neural networks) to find the best fit for your data characteristics.

Hyperparameter optimization using grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization fine-tunes algorithm behavior.

Ensemble methods combine multiple models through voting, stacking, or boosting, typically improving accuracy beyond individual models.

Address Class Imbalance

Imbalanced datasets require specific techniques:

Resampling oversamples minority classes or undersamples majority classes to balance training data.

Class weights penalize errors on minority classes more heavily during training.

Threshold adjustment changes classification boundaries to optimize for precision-recall trade-offs rather than raw accuracy.

Anomaly detection reframes problems with extreme imbalance as outlier detection rather than classification.

Handle Data Quality Issues

Poor data quality caps achievable accuracy regardless of modeling sophistication.

Missing value imputation fills gaps using statistical methods or learned patterns.

Outlier detection identifies and handles anomalous data points that distort model training.

Data validation ensures consistency, catching entry errors or measurement problems.

Feature scaling normalizes different measurement scales so all features contribute appropriately.

Cross-Validation and Regularization

Proper model evaluation and training techniques prevent overfitting that inflates training accuracy while generalization suffers.

Cross-validation provides more reliable accuracy estimates by testing on multiple data splits.

Regularization (L1, L2, dropout) prevents overfitting by constraining model complexity.

Early stopping halts training before overfitting begins, based on validation set performance.

Common Mistakes in Evaluating Model Accuracy

Avoid these pitfalls that lead to misleading accuracy assessments.

Focusing Only on Accuracy

Model accuracy alone rarely provides sufficient evaluation, especially with imbalanced data. Always examine precision, recall, confusion matrices, and domain-specific metrics.

Testing on Training Data

Evaluating accuracy on the same data used for training gives falsely optimistic results. Always maintain separate test sets or use cross-validation.

Ignoring Class Imbalance

High accuracy on imbalanced datasets may indicate a useless model that always predicts the majority class. Check class-specific performance metrics.

Overfitting to Test Data

Repeatedly tuning models based on test set performance causes overfitting to that specific data sample. Use validation sets for tuning and reserve test sets for final evaluation.

Neglecting Real-World Performance

Lab accuracy doesn’t always match deployment accuracy due to data drift, population changes, or integration issues. Monitor production performance continuously.

Comparing Different Metrics

Comparing your model’s accuracy against another’s precision or F1 score provides no meaningful comparison. Use consistent metrics across comparisons.

Misunderstanding Baseline Performance

Claiming “85% accuracy” means nothing without knowing the baseline. On an 85:15 imbalanced dataset, 85% accuracy just matches always predicting the majority class.

Ignoring Confidence Calibration

A model might achieve 80% accuracy but be wildly overconfident or underconfident in its predictions. Check probability calibration alongside accuracy.

Monitoring and Maintaining Model Accuracy Over Time

Machine learning model accuracy often degrades after deployment, requiring ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

Why Accuracy Degrades

Several factors cause model performance to decline:

Data drift: Input feature distributions change over time as user behavior, market conditions, or product offerings evolve.

Concept drift: The relationship between features and outcomes changes, making previously learned patterns obsolete.

Upstream changes: Modifications to data pipelines, preprocessing steps, or feature calculations alter inputs.

Adversarial behavior: In applications like fraud detection or spam filtering, adversaries adapt to circumvent detection.

Monitoring Strategies

Implement comprehensive monitoring to catch degradation early:

Performance metrics tracking: Monitor accuracy, precision, recall, and business KPIs continuously, alerting when they drop below thresholds.

Feature distribution monitoring: Track whether input feature distributions match training data distributions.

Prediction distribution monitoring: Ensure your model’s outputs maintain expected patterns.

Data quality checks: Validate incoming data for completeness, format consistency, and reasonable value ranges.

Retraining Strategies

Determine when and how to retrain models:

Scheduled retraining: Regular updates (weekly, monthly) on recent data keep models current.

Triggered retraining: Automatic retraining when monitoring detects performance drops below thresholds.

Continuous learning: Online learning algorithms update incrementally with each new data point.

Feedback loops: Incorporate user corrections and outcomes back into training data for continuous improvement.

Conclusion

Machine learning model accuracy cannot be judged in isolation—what’s “good enough” depends entirely on your specific application, business context, data characteristics, and the real-world consequences of errors. Medical diagnosis systems demanding 95%+ accuracy contrast sharply with recommendation engines, where 65% accuracy provides value, illustrating how context determines acceptable performance levels. Rather than chasing arbitrary accuracy targets, successful ML practitioners analyze error costs, evaluate multiple complementary metrics like precision and recall, establish meaningful baselines for comparison, and align model performance with business objectives.

Remember that 80% accuracy with a well-calibrated model understanding its limitations often outperforms a 90% accurate model deployed without considering class imbalance, data drift, or metric appropriateness—making proper model evaluation far more nuanced than comparing single percentage points. The journey to “good enough” accuracy requires balancing technical performance against practical constraints, continuously monitoring production systems for degradation, and maintaining realistic expectations about what machine learning can achieve within the inherent limitations of your data and problem domain.