What Is Cloud Native and Why Companies Are Switching

Learn what cloud native means, its core principles, benefits like scalability and resilience, and why companies are switching from traditional infrastructure to cloud native.

What is cloud native has become one of the most frequently asked questions in enterprise technology as organizations worldwide accelerate digital transformation initiatives seeking competitive advantages through faster software delivery, improved scalability, enhanced resilience, and reduced operational costs that traditional monolithic architectures and on-premises infrastructure simply cannot match in today’s rapidly evolving business landscape.

The term cloud native represents far more than simply moving applications to cloud platforms—it encompasses a fundamental architectural philosophy and set of practices built around microservices, containers, orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, DevOps methodologies, continuous integration and deployment pipelines, and infrastructure as code principles that collectively enable organizations to build and run scalable applications in modern cloud environments whether public, private, or hybrid.

The growing momentum behind cloud native adoption reflects compelling business realities—companies that successfully implement cloud native architectures report 50-80% faster time to market for new features, 60% improvement in deployment frequency, 90% reduction in infrastructure provisioning time, and significant cost savings through efficient resource utilization compared to maintaining legacy infrastructure and applications that scale poorly, update slowly, and require extensive manual intervention for routine operations.

Yet despite these impressive statistics, many organizations struggle to understand what cloud native actually means beyond buzzword status, how it differs from simply using cloud services, what practical steps the transition requires, and most importantly, whether the investment and organizational change justify the promised benefits for their specific circumstances.

This comprehensive guide demystifies cloud native technology, explaining the core architectural principles distinguishing it from traditional approaches, examining the key technologies enabling cloud native applications, analyzing the business drivers compelling companies to make the switch, addressing common challenges organizations face during migration, and providing practical guidance for determining whether and how your organization should pursue cloud native transformation to remain competitive in an increasingly digital economy.

Understanding Cloud Native: Definition and Core Concepts

Cloud native represents a comprehensive approach to building and running applications that fully exploits the advantages of cloud computing delivery models.

Defining Cloud Native

Cloud native applications are specifically designed and built to leverage cloud infrastructure characteristics and cloud platform services.

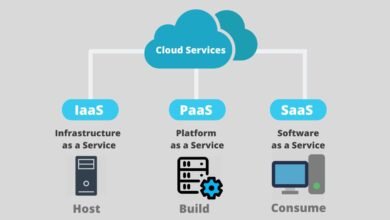

Formal definition: The Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) defines cloud native technologies as those that “empower organizations to build and run scalable applications in modern, dynamic environments such as public, private, and hybrid clouds.”

Key characteristics:

Built for cloud: Applications architected from inception to run in cloud environments, not retrofitted legacy applications.

Microservices architecture: Applications composed of small, independent services that communicate through APIs rather than monolithic codebases.

Containerization: Applications are packaged in lightweight containers, ensuring consistency across development, testing, and production environments.

Dynamic orchestration: Automated container management, scaling, and recovery through platforms like Kubernetes.

Declarative APIs: Infrastructure and application state defined through code specifying desired outcomes rather than step-by-step procedures.

Resilience by design: Built-in redundancy, failure handling, and self-healing capabilities.

Observability: Comprehensive monitoring, logging, and tracing enabling understanding of system behavior.

What cloud native is not: Simply migrating existing applications to cloud servers (“lift and shift”) without architectural changes doesn’t make them cloud native—they’re cloud-hosted but not cloud native.

Cloud Native vs. Traditional Applications

Cloud native applications differ fundamentally from traditional enterprise applications across architecture, development practices, and operational models.

Architectural differences:

Traditional (monolithic):

- Single deployable unit containing all functionality

- Componentsare tightly coupled and interdependent

- Vertical scaling (bigger servers) for increased capacity

- Single technology stack throughout the application

- Updates require testing and deploying the entire application

Cloud native (microservices):

- Multiple independently deployable services

- Loosely coupled components communicating via APIs

- Horizontal scaling (more instances) for capacity

- Polyglot architecture using the best tools per service

- Independent service updates without full redeployment

Operational differences:

Traditional infrastructure:

- Manual server provisioning (days/weeks)

- Static capacity planning based on peak load

- Infrequent major releases (quarterly/annually)

- Manual monitoring and intervention

- Long-lived servers requiring patching

Cloud native infrastructure:

- Automated infrastructure provisioning (minutes)

- Dynamic scaling matches actual demand

- Continuous deployment (multiple times daily)

- Automated monitoring with self-healing

- Immutable infrastructure replacing rather than updating servers

Core Cloud Native Principles

Cloud native success requires adhering to fundamental architectural and operational principles.

Essential principles:

1. Microservices architecture: Breaking applications into small, focused services with single responsibilities communicating through lightweight protocols.

2. Containerization: Packaging applications with dependencies into standardized units, ensuring consistency across environments.

3. Dynamic orchestration: Automated container lifecycle management, scaling, and service discovery through platforms like Kubernetes.

4. API-first design: Services exposing well-defined APIs enabling loose coupling and independent evolution.

5. Stateless processes: Applications storing state externally, allowing any instance to handle any request,t enabling horizontal scaling.

6. Declarative configuration: Infrastructure and application configuration defined as code specifyinthe g desired state rather than imperative scripts.

7. Continuous delivery: Automated pipelines enabling frequent, reliable software releases with minimal manual intervention.

8. Resilience and fault tolerance: Designing for failure with circuit breakers, retries, timeouts, and graceful degradation.

9. Observability: Instrumentation providing visibility into distributed system behavior through metrics, logs, and traces.

10. Infrastructure as code: Managing infrastructure through version-controlled code rather than manual configuration.

According to guidance from the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, these principles work synergistically—adopting one or two doesn’t deliver full benefits without broader architectural transformation.

Key Technologies Enabling Cloud Native

Cloud native architectures depend on several foundational technologies working together as an integrated ecosystem.

Containers and Docker

Containers provide lightweight, consistent runtime environments for packaging applications with dependencies.

Container fundamentals:

What containers are: Lightweight virtualization packaging applications with libraries, dependencies, and configuration files into isolated units.

Docker dominance: Docker became the de facto standard container format and runtime engine.

Benefits:

- Consistency: “Works on my machine” problems eliminated through identical environments across development, testing, and production

- Portability: Containers run identically on any infrastructure supporting container runtimes

- Resource efficiency: Containers share the host OS kernel, using fewer resources than virtual machines

- Fast startup: Containers launch in seconds versus minutes for VMs

- Isolation: Application dependencies and conflicts contained within containers

- Microservices enablement: Containers provide ideal deployment units for microservices

Container images: Immutable templates defining container contents built through Dockerfiles specifying base images and configuration steps.

Container registries: Repositories (Docker Hub, Amazon ECR, Google Container Registry) storing and distributing container images.

Kubernetes and Container Orchestration

Kubernetes automates the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications at scale.

Kubernetes capabilities:

Container orchestration: Automated deployment and management of hundreds or thousands of containers across server clusters.

Key features:

- Automated scheduling: Placing containers on appropriate nodes based on resource requirements

- Self-healing: Restarting failed containers, replacing containers, killing unresponsive containers

- Horizontal scaling: Adding or removing container instances based on CPU utilization or custom metrics

- Service discovery: Automatic DNS and load balancing for services

- Rolling updates: Gradually updating applications without downtime

- Configuration management: Storing and managing sensitive information like passwords and API keys

- Storage orchestration: Automatically mounting storage systems

Kubernetes architecture: Master nodes managing cluster state; worker nodes running application containers; control plane components coordinating operations.

Managed Kubernetes: Cloud providers offering managed Kubernetes services (Amazon EKS, Google GKE, Azure AKS), reducing operational burden.

Complexity consideration: Kubernetes provides tremendous power but significant complexity—necessary for large-scale deployments but potentially overkill for simple applications.

Microservices Architecture

Microservices structure applications as collections of loosely coupled, independently deployable services.

Microservices characteristics:

Service independence: Each microservice is a separate codebase, data store, and deployment unit.

Business capability focus: Services organized around specific business functions (user management, payment processing, inventory) rather than technical layers.

Decentralized governance: Teams choosing appropriate technologies and patterns for their services.

Benefits:

- Independent deployment: Update individual services without redeployingthe entire application

- Technology flexibility: Different services using different languages, frameworks, and databases

- Team autonomy: Small teams owning services end-to-end

- Resilience: Service failures are isolated, not cascading through the entire application

- Scalability: Scale individual high-demand services independently

Challenges:

- Increased operational complexity (many services to manage)

- Distributed system complexity (network latency, partial failures)

- Data consistency across services

- Testing across multiple services

- Service communication overhead

Service mesh: Technologies like Istio provide service-to-service communication, security, and observability without changing application code.

DevOps and CI/CD Pipelines

DevOps practices and automation pipelines enable rapid, reliable software delivery, fundamental to cloud native benefits.

DevOps integration:

Cultural shift: Breaking down walls between development and operations teams for shared responsibility.

Continuous Integration (CI): Automatically building and testing code changes when developers commit code.

Continuous Deployment (CD): Automatically deploying tested changes to production environments.

Pipeline stages:

- Code commit triggers pipeline

- Automated build compiles code

- Automated tests verify functionality

- Security scanning identifies vulnerabilities

- Container image creation

- Deployment to staging environment

- Integration and performance testing

- Automated deployment to production

- Monitoring and observability

Infrastructure as Code (IaC): Managing infrastructure through version-controlled code (Terraform, CloudFormation), enabling reproducible, auditable infrastructure changes.

GitOps: Using Git as a single source of truth for infrastructure and application configuration with automated synchronization.

Serverless Computing

Serverless represents the extreme evolution of cloud native thinking—abstracting infrastructure completely.

Serverless characteristics:

Function-as-a-Service (FaaS): Running code functions in response to events without managing servers.

Key platforms: AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions, Azure Functions.

Benefits:

- Zero infrastructure management

- Automatic scaling from zero to thousands of concurrent executions

- Pay only for actual execution time (sub-second billing)

- Built-in high availability

Limitations:

- Cold start latency when functions haven’t run recently

- Execution time limits (typically 5-15 minutes maximum)

- Vendor lock-in concerns with proprietary APIs

- Debugging complexity in distributed event-driven systems

Use cases: APIs, data processing, real-time file processing, scheduled tasks, IoT backends.

Why Companies Are Switching to Cloud Native

Cloud native adoption accelerates as organizations recognize compelling business and technical advantages over traditional architectures.

Faster Time to Market

Cloud native practices dramatically accelerate software delivery, enabling competitive advantages.

Speed improvements:

Continuous deployment: Leading cloud native organizations deploy code changes hundreds or thousands of times daily versus monthly/quarterly releases for traditional applications.

Reduced cycle time: Automated pipelinesreduceg time from code commit to production deployment from weeks to minutes.

Parallel development: Independent teams working on separate microservices simultaneously without coordination bottlenecks.

Experimentation velocity: Rapidly testing new features with subsets of users, quickly rolling back if unsuccessful.

Market responsiveness: Quickly adapting to market changes, customer feedback, and competitive threats.

Real-world example: Netflix deploys code changes 1,000+ times daily; Amazon deploys every 11.6 seconds on average—velocity impossible with traditional monolithic applications and manual deployment processes.

Business impact: Faster delivery means capturing market opportunities before competitors, responding to customer needs quickly, and continuously improving products.

Improved Scalability and Performance

Cloud native architectures scale efficiently, meeting variable demand without over-provisioning.

Scalability advantages:

Horizontal scaling: Adding more service instances rather than upgrading to larger servers—cheaper and more flexible.

Auto-scaling: Automatically adding capacity during traffic spikes, removing during low usage—paying only for needed resources.

Granular scaling: Scaling specific high-demand services independently rather than the entire application.

Geographic distribution: Deploying services across multiple regions for global performance.

Resource efficiency: Containers use resources more efficiently than virtual machines.

Performance optimization: Microservices architecture enabling technology choices optimized per service (in-memory database for cache, specialized search engine for queries).

Cost efficiency: Right-sizing resources to actual demand rather than maintaining capacity for peak loads.

Example: E-commerce site automatically scaling payment services 10× during holiday shopping while keeping other services at normal capacity.

Enhanced Resilience and Reliability

Cloud native design patterns build resilience into applications from an architectural foundation.

Resilience features:

Failure isolation: Microservices architecture containing failures within services rather than cascading through the entire application.

Automatic recovery: Kubernetes restarts failed containers, replaces unhealthy instances, redistributing load.

Circuit breakers: Preventing repeated calls to failing services, allowing graceful degradation.

Redundancy: Running multiple instances of services across availability zones and regions.

Chaos engineering: Deliberately injecting failures in production to verify resilience.

Zero-downtime deployments: Rolling updates gradually replace instances with new versions.

Self-healing: Systems automatically detecting and recovering from failures without human intervention.

Improved uptime: Organizations report 99.95%+ availability with cloud native architectures versus 99.5% or lower with traditional monoliths—a difference between 4 hours and 44 hours of annual downtime.

According to research from Google Cloud, organizations adopting cloud native architectures report 60% fewer outages and 200× faster incident recovery times.

Cost Optimization

Cloud native architectures enable significant cost reductions through efficient resource utilization and automation.

Cost benefits:

Pay-per-use: Cloud providers charge only for resources actually consumed rather than maintaining capacity for peak loads.

Resource efficiency: Containers use 50-80% less resources than virtual machines for equivalent workloads.

Auto-scaling: Automatically removing unnecessary capacity during low-usage periods.

Reduced infrastructure management: Managed Kubernetes and serverless options, eliminating server management overhead.

Faster development: Developer productivity improvements reduce time (and cost) to build and modify applications.

Lower operational costs: Automation reduces manual operations

Infrastructure optimization: Right-sizing resources based on actual monitoring data.

Example calculation: Traditional infrastructure maintaining capacity for peak load might average 30% utilization; cloud native with auto-scaling, achieving 70%+ utilization,n saves 50%+ on infrastructure costs.

Innovation and Competitive Advantage

Cloud native capabilities enable innovation and experimentation difficult with traditional architectures.

Innovation enablement:

Rapid prototyping: Quickly building and testing new features or products with minimal infrastructure investment.

A/B testing: Easily deploying alternative implementations to subsets of users and measuring which performs better.

Feature flags: Enabling/disabling features without deploying code changes.

Experimentation culture: Low-risk, fast feedback loops encouraging innovation.

Technology flexibility: Adopting new languages, frameworks, or databases for specific services without rewriting the entire application.

Developer satisfaction: Modern development practices and tools are attracting and retaining top engineering talent.

Time-to-innovation: Reducing time from idea to customer-facing feature from months to weeks or days.

Competitive necessity: As competitors adopt cloud native, maintaining traditional architectures becomes a competitive disadvantage.

Common Challenges in Cloud Native Adoption

Switching to cloud native requires overcoming significant technical and organizational challenges.

Complexity Management

Cloud native systems introduce architectural and operational complexity.

Complexity sources:

Distributed systems: Microservices create networks of services with complex interactions, debugging challenges, and consistency issues.

Technology proliferation: Kubernetes, service meshes, monitoring stacks, CI/CD tools—many new technologies to learn and integrate.

Operational overhead: Managing hundreds of microservices versus a single monolithic application.

Observability needs: Understanding distributed system behavior requires sophisticated monitoring, logging, and tracing.

Network complexity: Service-to-service communication, security, and failure handling.

Mitigation strategies:

- Starting small with pilot projects

- Investing in training and knowledge building

- Adopting managed services rreducesoperational burden

- Implementing comprehensive observability from the art

- Using service meshes simplifies service communication

Skills Gap and Cultural Change

Cloud native success requires new technical skills and organizational culture changes.

Skill requirements:

Technical skills needed:

- Container technologies (Docker)

- Kubernetes and orchestration

- Microservices architecture patterns

- DevOps practices and tools

- Infrastructure as code

- Cloud platform expertise

- Programming skills for automation

Cultural shifts:

- DevOps collaboration versus siloed teams

- Embracing failure and learning from it

- Automation over manual processes

- Shared responsibility for production systems

- Continuous improvement mindset

Addressing skills gaps:

- Training existing staff

- Hiring experienced cloud native engineers

- Partnering with consultants for initial projects

- Building centers of excellence

- Allowing learning time and experimentation

Migration Strategy

Moving existing applications to cloud native architectures requires careful planning and phased approaches.

Migration approaches:

Strangler fig pattern: Gradually replacing monolith functionality with microservices, running both in parallel during transition.

Start with new features: Building new capabilities as microservices while maintaining the existing monolith.

Extract high-value services: Identifying components benefiting most from cloud native characteristics and migrating those first.

Containerize first: Putting a monolith in containers as an intermediate step before microservices decomposition.

Big bang rewrite: Complete rewrite (generally not recommended due to risk and cost).

Migration considerations:

- Data migration and consistency during transition

- Service integration between legacy and new systems

- Performance testing throughout migration

- Team capacity for maintaining existing systems while building new ones

- Budget and timeline realism

Getting Started with Cloud Native

Beginning cloud native transformation requires a strategic approach, balancing ambition with pragmatism.

Assessing Readiness

Organizations should evaluate whether they’re ready for cloud native transformation.

Readiness factors:

Business drivers: Clear business reasons (speed, scale, innovation) justifying investment.

Executive support: Leadership commitment to multi-year transformation.

Team capability: Technical skills or willingness to develop them.

Application suitability: Applications that benefit from cloud native characteristics.

Budget availability: Financial resources for tools, training, and potential consultants.

Cultural alignment: Willingness to embrace DevOps, experimentation, and change.

Starting point determination: Not all organizations need full cloud native transformation—assess what level of adoption serves your needs.

Practical First Steps

Starting cloud native journey with manageable, low-risk initiatives builds confidence and skills.

Recommended approach:

1. Education: Training teams on cloud native concepts, technologies, and practices.

2. Pilot project: Selectinga small, non-critical application for initial cloud native implementation—learning without risking the core business.

3. Containerization: Beginning with containerizing existing applications, even without microservices decomposition.

4. CI/CD pipeline: Implementing automated build and deployment pipelines for faster, more reliable releases.

5. Cloud platform selection: Choosing between AWS, Google Cloud, Azure, or multi-cloud based on requirements.

6. Monitoring and observability: Implementing comprehensive monitoring fromthe start.

7. Incremental expansion: Gradually expanding cloud native adoption based on lessons learned.

8. Celebrate wins: Recognizing successes, building momentum for broader transformation.

Choosing Cloud Native Tools

Cloud native ecosystem offers numerous tools requiring careful selection.

Key technology decisions:

Container orchestration: Kubernetes dominates but adds complexity—evaluate whether simpler options (AWS ECS, Cloud Run) suffice.

CI/CD tools: Jenkins, GitLab CI, GitHub Actions, CircleCI, or cloud-native options.

Monitoring stack: Prometheus, Grafana, commercial APM tools, or cloud provider monitoring.

Service mesh: Istio, Linkerd, or skipping iinitiallyy depending on the complexity needs.

Infrastructure as code: Terraform, Pulumi, or cloud-provider tools (CloudFormation, ARM templates).

Selection criteria:

- Team expertise and learning curve

- Integration with existing tools

- Community support and ecosystem

- Vendor lock-in concerns

- Cost considerations

- Managed service availability

Conclusion

What is cloud native fundamentally represents a modern approach to building and operating applications that fully exploits cloud computing advantages through microservices architectures, containerization, orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, DevOps practices, and automated infrastructure management—enabling organizations to develop and deploy software faster, scale more efficiently, improve resilience and reliability, optimize costs, and drive innovation at speeds impossible with traditional monolithic applications and on-premises infrastructure.

Companies are switching to cloud native driven by compelling business imperatives including 50-80% faster time to market for new features enabling competitive advantages, 60% improvement in deployment frequency supporting rapid experimentation and customer responsiveness, dramatic scalability improvements allowing applications to automatically handle traffic spikes while reducing costs during low-usage periods, 99.95%+ availability through failure isolation and self-healing capabilities versus frequent outages plaguing traditional architectures, and significant cost savings through efficient resource utilization and reduced operational overhead.

However, successful cloud native adoption requires acknowledging substantial challenges including architectural complexity from distributed microservices systems, operational overhead managing many independent services, significant skills gaps requiring training or hiring cloud native expertise, cultural transformations embracing DevOps collaboration and automation over traditional siloed approaches, and careful migration strategies gradually transitioning existing applications to cloud native architectures through patterns like strangler fig rather than risky big bang rewrites.

Organizations considering cloud native transformation should begin with honest readiness assessments evaluating business drivers, executive support, team capabilities, and cultural alignment before starting with manageable pilot projects that build skills and confidence, gradually expanding adoption based on demonstrated success while recognizing that cloud native represents not a destination but a continuous journey of improvement and optimization that, when done thoughtfully, positions companies to compete and innovate effectively in increasingly digital markets where speed, scale, and adaptability determine winners and losers.